La Vida Loca

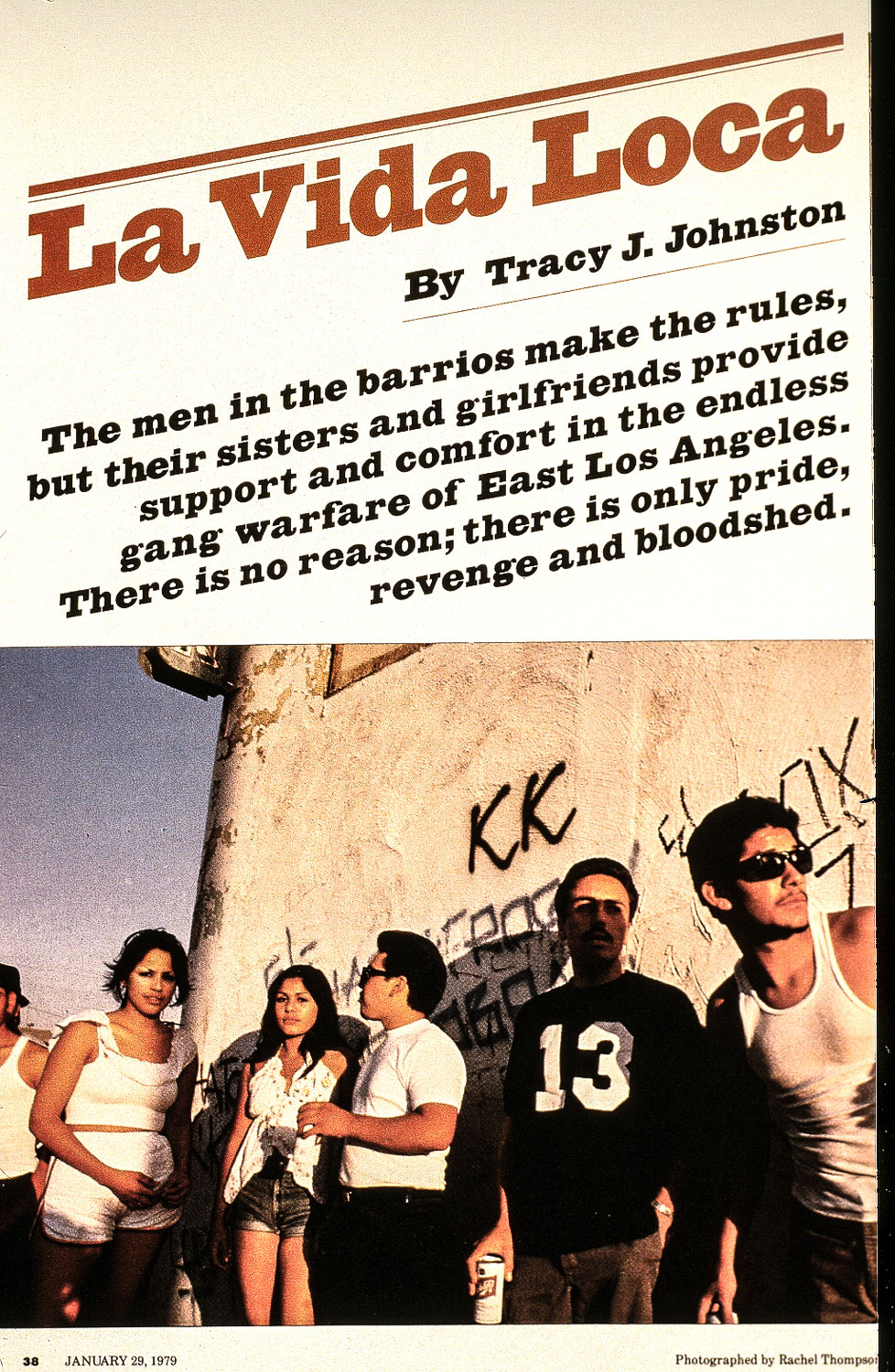

By Tracy J. Johnston. Photographs by Rachel Thompson.

Published in New West Magazine, January 28, 1979

SPIDER HAD HIS MELANCHOLY EXPRESSION TONIGHT, the one that always made Loca feel sorry for him. His brown eyes looked so sad that she forgot about the ways he treated her bad, the times he messed up on her with other girls, the nights he left her to go out shooting. He was a vato loco, a crazy guy in the barrios, but it was because he didn't give a fuck about life. When he was thirteen and got busted by the cops he found out that the person he loved as his mother was actually his grandmother. His mother was Marianna, the sister who looked after him only when she had the inclination and the time.

The hallucination happened when they were sitting on the back porch of his grandmother's house, tripping on angel dust (PCP). It was a warm night in December and Loca felt good. She liked getting dusted with Spider because it made her feel as if she could do anything; as if she were better than everyone else even though she was only a chola in the barrios. It even made her want to go shooting with the guys. She knew they wouldn't let he but just the thought of it was exciting.

Sometimes, when she and Spider were dusted, they would get so close it was like they were one person. He would say something funny to make her laugh and then he would act all mean to make her cry and then he would be all sad and she'd be all sad as well and start thinking about her own problems. Spider sometimes hit her, but she didn't mind because he didn't hit her for nothing; she always did something to deserve it. And Spider loved her. She knew it because she broke up with him twice, and each time he came back to her crying.

"Hey, Spider." Loca said when suddenly everything changed on that back porch. "SPIDER?" SPIDER? Something was wrong! She could see he was scared because he was looking at her as if she had become the devil. He leaped to his feet, grabbed her arm and tried to twist it behind her back. When she yelled "SPIDER IT'S ME!" he looked at her with an expression that made her stomach turn. Then he turned and ran inside the house.

Loca stayed on the porch for a moment, feeling confused and sick to her stomach. Why did Spider have to ruin everything? But then she realized he might need help so she made herself go inside. First she went to the glass cabinet in the dining room and found a rosary next to his grandmother's collection of saints. Although she never went to church, she took out the rosary and prayed to God that Spider would be all right. Then she went to Spider's room and peeked inside. He had ripped the medallion of Saint Christopher off his neck — the one she gave him — and was holding it in both hands.

Later that night, Loca held Spider in her arms, and cradled him as if he was a child. She felt strong because she was holding a soldier in the barrio, a wild and impulsive and crazy man. Before she went home, they both knelt down and prayed to God for forgiveness. They would settle down and give up la vida loca, "the crazy life." They would get married in June.

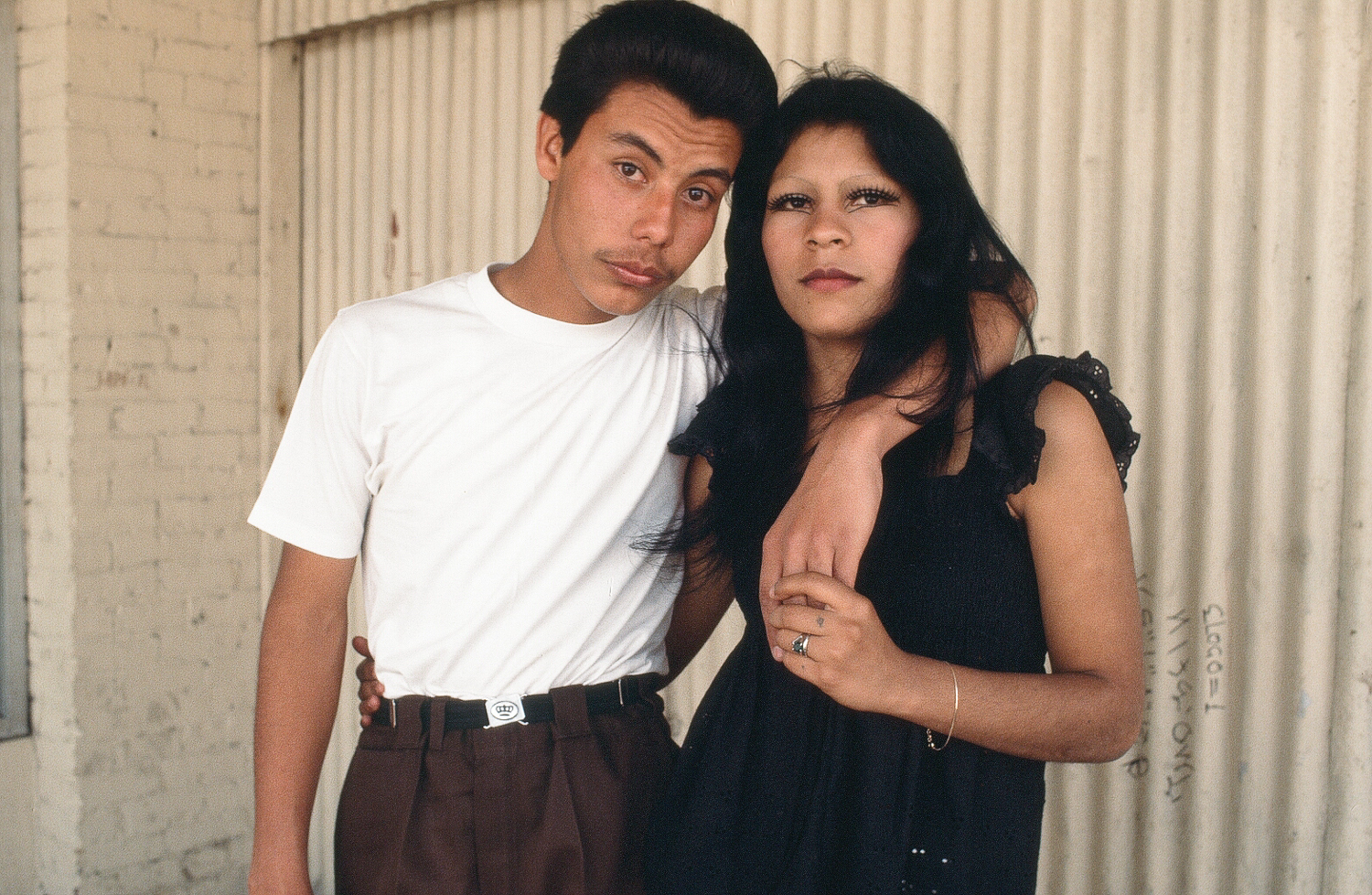

*Please note: the photos were taken in the barrio but not of the story's subjects.

Spider's promises lasted for one night. The next morning, when Loca met him in the park, he acted as if it had all been a joke — just too much angel dust or maybe dust that had been poisoned by an enemy gang. But then, three days later, on New Year's Eve, all the home girls and home boys got together at Pedro's place and had the best party of their entire lives. At about three in the morning the girls went outside and yelled, "PEREZ MARAVILLA RIFA" (Perez Maravilla barrio rules). They stopped only when the guys came out and told them to shut up because the screaming might attract the cops. It was a great night, Loca said, because the guys and girls were all together and everyone was leading the crazy life.

Two weeks after the party, Loca got a call from the East Los Angeles sheriff's office and Spider got on the phone. He said he'd been busted with some of the home boys, for carrying a gun. They had been set up, he said, because the gun wasn't his. When Loca realized what that meant, she started crying and had to hang up. Spider would be in jail for months. But then she got mad and decided to go to the park and look for someone to fight. She was big for a Chicana and she never lost a fight unless other girls jumped in. But before she found any girls she saw some of Spider's home boys sitting on the grass waiting to play soccer, as if nothing had happened. .

"YOU CALL YOUR SELF HOMEBOYS!" She yelled. "BUT YOU KNEW THAT SPIDER IS ON PROBATION AND THAT IF GOT BUSTED HE COULDN'T GET OUT, AND YOU TOOK HIM ALONG SHOOTING ANYWAY. YOU DON'T CARE ABOUT SPIDER. HE'S YOUR HOMEBOY AND YOU DON'T CARE ABOUT HIM. I'M TIRED OF THE BARRIO. IT'S SUPPOSED TO MEAN THAT YOU HAVE FRIENDS TO BACK YOU UP IN A FIGHT AND TAKE YOU IN IF YOU NEED A HOME. BUT LOOK WHAT YOU DID TO SPIDER. NOW HE DOESN'T HAVE NOTHING!

When Loca stopped yelling, Spider's best friend, Payaso, got up and walked over to her. He put his arm around her and turned her away from the other guys."You know there's no way anyone can tell Spider what he can or cannot do," he said. "We didn't make him go."

Loca knew what Payaso said was true. "But he'll be in jail for at least eight months," she cried.

"Come on, let me take you home. Spider loves you. Last night in the car, just before we got busted, he said that before anything happened to him he wanted you and him to get married."

"If he loves me so much, why did he go shooting?"

"That's his business," Payaso said. You can wait.

* * *

WHEN LOCA TOLD ME THIS STORY, SIX YEARS LATER, she seemed envious. Those were the days when no one could tell her what to do, when being Spider's woman made her someone special. Now everything had changed. She was married to Spider and she had two babies, Fernando, 2, and Michael, 1. They lived in his mother's apartment in a building that looked like an army barrack in one of the poorest of the East Los Angeles projects. In the tiny living room where Loca and I sat there were few of the touches that grace almost every other barrio home — no plastic flowers, no dolls in frilly dresses, no crimson-and-gold shrines to the Virgin of Guadalupe. The television and stereo were big and functional, but the other two pieces of furniture — a chair and couch — were ragged.

"I don't even leave this room during the day, " Loca says. I don't like to take the babies on a bus and Spider won't buy me a car." Loca now spends her days watching soap operas, listening to her 45 collection, and playing with her babies. At night, when Spider comes home from his job working for his uncle, they go upstairs to their bedroom and watch cops-and-robber shows on television. At least once and usually twice a week, Spider presses his khaki pants, puts on his small-brimmed felt hat, and goes out to spend the night partying with his home boys.

The move from virgin to mother is made quickly in the barrios.

"Maybe I should have known that I'd be like all the rest," Loca says, "but I thought Spider was different. He's good to me in some ways—he provides for me and the babies. I think it's his mother that puts a lot of shit into his head. I didn't really know much about her until Spider said we'd have to live with her because she needs the money to pay the rent. I don't like her—she goes out to bars and comes home with guys that are just as young as Spider. When Spider started going out on me at night I got mad, but whenever I argued with him his mother would butt in and tell him not to listen to me—right in front of my face. 'You're a man,' she says, 'and you can do whatever you want. The women are supposed to listen to you; you don't have to listen to them.' Now I tell her what I think. I argue back. I'm ashamed because I don't show her no respect, but I don't care anymore. I tell her, 'You're thinking about centuries ago; man, that stuff is dead. We don't live that way no more.'".

"I guess with his mother talking bad about me and him being out all the time, I lost my love for Spider. I'm just happy I had the babies because they got me off drugs. Spider and I, we don't have no relationship no more. I just huddle over on my side of the bed. Sometimes we talk about it and he says he thinks he was too young to get married. I say, 'Why didn't you think about that before? You're 25, I'm only 19. Why am I the one who has to become an old lady?"

* * *

NEGRA, CHICA AND SHORTY ARE JUST LIKE LOCA WAS SIX YEARS AGO. They are fifteen and proud of who they are. They have seen their mothers grow hysterical with too many children and no money; their fathers get mean on booze and drugs; their uncles bloody each other up with broken bottles and fistfights. But now they have a new family, their barrio gang. They still give superficial signs of respect to their parents — both Chica and Negra don't swear or smoke at home — but in most ways they have left their families to join the home boys and home girls of Segundo Flats.

When I arrive for a scheduled interview, the three girls are sitting on Shorty's front porch, drinking beer and in no mood to talk about their future. Just before I arrived they had sneaked into Shorty's brother's room, put paper bags over their heads and sniffed his spray paint. And before that they were out on Brooklyn Avenue kicking ass with two girls from Lorca Street.

SHORTY is the baddest looking of the three girls. She is big with tattoos on her arms and shoulders, and she still wears an enormous amount of makeup— even though the style is on its way out. The makeup, called masks or máscaras, is — like tattoos, murals and, graffiti — a peculiarly Chicano style of self-expression. All the girls pluck out their eyebrows and pencil in thin new ones that rise like arches high on their foreheads, and paste on long black eyelashes that give their toughness an odd, feminine touch. Shorty, however, paints a white mask around her eyes, from the top of her cheekbones up to her eyebrows and all the way out to her hairline. The effect is best described as "Raccoon."

Shorty seems unfazed by my presence and comfortable with herself. I've heard her story from Negra. She has an older brother in Segundo Flats who is a crazy, a wild-man, a vato loco who does a lot of shooting and is a hero to younger boys. Her mother is trying to keep her other six kids out of the gang wars, but it's an impossible task for a woman. Since her husband left, her eldest son, the vato, has taken over as head of the household. When I ask Shorty later about her brother, she says, "My brother is a monster, but he is also my king.”

NEGRA is the prettiest of the three girls. She has red cheeks, clear ivory skin, and dark, almost black eyes. She looks like the dolls that Chicana women prop up over their fireplaces. Negra's mother abandoned her and L'il Man, her brother, when she was four so now she lives with her aunt and uncle, grandmother and grandfather, in a two-bedroom house where the furniture and lampshades are covered with clear plastic. Negra doesn't know much about this family. Her grandparents lived in Mexico but she doesn't know in which town or even which state. Her uncle has a well-paying job in a factory, but she doesn't know what he does or what the factory makes. “I mind my own business," she told me. "I don't ask questions."

CHICA is the least chola looking of the three girls, and also the smartest and most likely to "straighten up." She is the only chola I've met who gets better than Cs and Ds in school.

Chica's father is a former vato loco in Segundo Flats who survived all the warfare, but just barely. Although he's always had a $300-a-week factory job, he's been addicted to heroin for most of his life. Chica says she keeps telling her mother to throw him out of the house, but the two times her mother did it he came back to her crying and she took him back.

"A few months ago I tried to have it out with him," Chica confided. "He was all—like that—you know, and I ran away from home and stayed at my boyfriend's house for a few days. I guess I wanted my father to straighten up and come and get me; but he didn't. Finally I gave up and went home by myself, and called me a tramp for staying at my boyfriend's house. When I told him I didn't do nothing and slept in another bedroom—he didn't believe me. He called me a whore and got out a knife. I was crying and crying and I felt like leaving again, but then he went into this thing where he said he was tired of life and was going to kill himself. I felt real bad then because I thought it was because of me. But my mother told me not to feel guilty. She said, 'He's been tired of life since he was fifteen."

I would say I hate my father because he's mean to me and he don't trust me. But inside I know I love him because I'm going to do what he told me: “finish high school, don't get pregnant, don't be like I am.” You might call me a veterana someday because I gangbang now and all, but I'm not going to be like a lot of them. I know how it is. You get pregnant and then you have to get married. And your husband goes out on you and when you want to go someplace you have to borrow a car. My boyfriend wants me to marry him after I finish high school, but I say, 'I'm not going to finish school for a while. I want to be a counselor and that takes some college.' He says, 'But I can support you,' and I say, 'On $200 a week?' He says, 'Yeah' and I say, "'Uh-uh. That's not enough.' "

As I sit with Shorty, Negra and Chica on the porch this afternoon I am ignored but tolerated with good humor. They tell the story of their fight over and over again and each time their roles getting more heroic. Although the fight was broken up by a security guard soon after it started they all agree that they were down on the ground getting dirty and kicking ass. As I listen to them talk, laugh and giggle with delight, the way I did when I was fifteen and something made me feel big and important, I remember my conversation with Rachel Ruiz. Rachel is a Chicana community organizer who took me into the heart of the barrios. She warned me that cholas would try and make their life seem glamorous.

"Don't let them tell you that their life is exciting," she said. "These girls have absolutely nothing to do. They fight for one day and hang around for twenty. The girls are mothers, the guys are fighters, and that's it. The girls have no models of women doing anything interesting or positive. If they have any ambition they want to be a probation officer, a policewomen, or a counselor. That's all they know. People don't grow up here. It's an adolescent culture—full of petty jealousies, paranoia, macho bravado. It's a defeated culture, really. The men think they are shit, and the women are even lower than the men."

Right now, Negra, whose eyes are slightly out of focus, is flying: "That girl with the big old tattoo on her neck that says Lorca Street? When I asked her de dònde [Where are you from?] she says, 'Nowhere.' Fuck. Who does she think we are, man? When she's with her sister she's from Lorca Street. I saw her sister and her in a fight once and she was kicking ass."

"I hate everyone of those guys from Lorca Street," says Shorty. "They ain't even in their own neighborhood and they think they're big shit. We gotta tell the guys to take care of business. They come in here and think they can go anywhere they want. Dopey said she saw a guy from Lorca Street right down there by the gym and no one did nothing to him."

"He's probably on his way to see Yo," says Chica. “Guys from Lorca Street can't get it anywhere else.

Both Chica and Shorty are laughing now, and Negra has to shout to make herself heard.

"Hey, wait a minute, WAIT A MINUTE! WHO'S YO? AND WHAT THE FUCK DOES YO DO?"

"What do you think, Negra?" "She give' em everything."

"What's everything."

"BLOW JOBS."

“What's that?”

“UNA MAMADA, dummy.”

"E-e-e-e-e yuk!" Negra says and makes a vomiting motion. (Everyone laughs.)

"Yo wants it," Shorty says. "My brother says there's girls like that. They get raped when they're real young and they learn to like it and they can't get enough of it."

"Ain't no one gonna rape me," says Chica.

"What you gonna do about it?" says Negra. "You get all loaded some night and he's got you alone and your home boys don't care?"

"You say, 'I always wanted a mamada, honey. Here, first take out this.''' (Shorty holds up an imaginary Tampax.)

By this time I'm caught up in the sheer energy of the girls' dirty talk and the intense edge the drugs have given it. "Hey," I say, joining them for the first time. "How much do you girls know about sex?"

They stop laughing and look embarrassed. "We know everything," says Shorty. "We know it all."

"Do you know about orgasms?"

Silence.

"What is it?" says Chica. Negra and Shorty look down at the ground. Somehow I'm stuck with explaining.

"My sister," says Shorty, "says she doesn't feel nothing."

"I'm scared of sex," says Chica. "I ain't gonna do it until I get married."

"I know all about sex that I have to know," says Negra. "What happens when it's over, man. You feel like you want to throw up."

* * *

FOR MOST DRIVERS IN THE CITY OF THE ANGLES, THE INTERSECTION WHERE FIVE FREEWAYS COME TOGETHER is a terrifying swirl of lanes and arrows, speed, concrete, that lead to fantasy destinations: Hollywood, Pasadena, Santa Monica, Long Beach. The San Gabriel Mountains rise up to the north; the beach is 40 minutes west; Disneyland is a half-hour away, and the tall buildings of the old city center are practically close enough to touch. But for the people who live in the small, wooden, two-bedroom houses that lie low around the intersections, the freeways are no more than scars across the land they call home. Despite the speed and movement that surround them, the Mexican-American barrios of East Los Angeles have remained unchanged since the l930s. They are still the mecca for Mexicans coming to California from the northern high deserts of Mexico, and a place where a violent subculture based on continuing gang warfare has thrived amid poverty and dislocation. It is a subculture that is lower-class Mexican, rural, and macho; isolated from the rest of Los Angeles Chicano culture and at least twenty years behind Mexican-American culture in general. In each barrio, which may have anywhere from 100 to 2,000 families, there are only about 30 to 50 men of fighting age (11 to 30) who define the territory and keep the warfare going. Called pachucos in the 1940s, they are now called cholos. They call themselves vatos locos, or crazy guys.

The vatos locos live out their lives much the way their forefathers did when they first came to Los Angeles from Mexico via Arizona and Texas. They are overwhelmed by the wealth that surrounds them, and by the poverty and sorrow that seem to be their fate. Rather than shuffle around in disgrace, they choose to lead la vida loca, where they can at least be defiant and get a reputation for risking their lives without flinching and taking drugs without caution. Where they can die the most glorious death of all – the death of a soldier fighting for his barrio. There were 24 deaths from gang warfare in this seven-and-a-half square-mile area last year. In their own fantasies, the vatos locos are Homeric heroes: soldiers in an ancient battle whose origin is unknown. They settle their problems with guns and sacrifice themselves for altruistic codes— of revenge and loyalty and honor. But they are also ghetto boys who live in the worst pocket of poverty, unemployment, drug abuse and family disintegration in the West. Supported first by their families, then by relatives, the hardcore vatos spend their days hanging out, talking to each other, living in the past, alternately protecting and bullying their sisters, mothers and girl friends, fighting and reliving their fights in endless detail. And always, always, getting high.

I have emphasized the men in explaining gang warfare because they do the killing; they make up the rules. But there are women in the barrios who also believe in holding up the tattered remnants of this distorted pride. As mothers, they bring up their sons to think they must get "a reputation" in order to "be a man." As sisters and girlfriends, they support the vatos by forming girl gangs that are like women's auxiliaries. The girls often go through a period, from age eleven to thirteen, of trying to act like the guys—painting their faces and tattooing their bodies in order to look "bad." Some even go through a stage of dressing cholo—starched khaki pants, white T-shirts, Pendleton shirts worn as a jacket, and a headband just over the eyes.

As with Loca, however, this stage is short-lived. Very soon they fall in love with a home boy who tells them he wants to get married. After that, they have his baby because only whores use the Pill and only cowards have abortions. For a while they bask in the rewards of pregnancy — people treat them with respect, their mothers don't hate them anymore, guys don't try to hit up on them or give them drugs. Then they start to worry about the rest of their lives.

The girls like Loca were not hard to find. Many of them were angry—disgusted with the vatos and eager to get an education, a job, and a day-care center to take care of their kids. But there are also girls at the dead center of the gang culture who know no other way of life and are fearful of the world outside. They are often good mothers and close to their families who give them a lot of love and support. Rachel Ruiz said she would introduce me to a girl in Yellow Rock barrio, one of maybe four or five barrios in East L.A. that are small, isolated from the rest of the world, and closed to outsiders. "Jeanette," Rachel said, "is Stone Barrio. Although the world is changing around her, she cannot see it, and does not dream of a future that will be different from the past. She was born into a family of gang warriors and from the age of three she started hating the world outside her neighborhood for killing her brothers and cousins."

* * *

I WAS SHOCKED WHEN I FIRST SAW JEANETTE. I had expected her to look "badder," even, than Shorty. But instead, she looked like a college girl — pretty, feminine, and smart. The three of us meet in the basement of Jeanette's house—a spacious, windowless room that was, for many years, a Yellow Rock hangout. But now most of Jeanette's brothers and cousins are either dead, in prison, or born-again Christians so the basement is no longer the center of shooting-strategy sessions and there are no parties there anymore. Joints of angel dust and marijuana are forbidden. Nevertheless, the basement is still bustling. When we take a break from talking, it fills up with children who turn on the radio, bring ice cream cones from the neighborhood store, and sit around on the old couches and mattresses laughing and talking. When toddlers and young children wander in and out they are hugged and played with affectionately by both the girls and the boys. Clearly no one in Yellow Rock grows up lonely or uncared for, like Negra, Chica, and Shorty.

Jeanette tells me that she thinks the girls in Yellow Rock are different from the girls in other barrios. They don't have nicknames, they don't call themselves home girls, and they don't dress or make themselves up to look bad.

"We have respect," she says with pride. "The guys listen to us, they really do."

"Why is that?"

"We've grown up with them since we were little. We fought them and beat them up. They know we can take care of business."

"I heard that the girls from Yellow Rock are pretty," I say.

"I know that's what they say. If you can handle your stuff you don't need to look bad. We just laugh at the cholas who try and act like the guys. To me, they look dumb. All that makeup and their eyebrows plucked out."

Jeanette, herself, is delicate and slim. She smokes her cigarette like Lauren Bacall.

"Do you think you'll get married?" I ask. "You're twenty years old; isn't that time to be settling down?"

"I am settled down," she says. "There aren't many guys left to choose from."

"Guys in Yellow Rock?"

"Most of them are either married, dead, in jail or all scarred up. Some of them are dusted every day."

"Do you have to marry a guy from Yellow Rock?"

"No."

"Would the guys let you marry someone from another barrio?"

"They couldn't stop me."

"Would you do it?"

"No."

"Why not?"

"It's too much trouble. The guys would kill him if he came to live here, and if I moved into his neighborhood no one would talk to me. I know how it is because I've seen the way we treat the wives from other neighborhoods who move in. No one will talk to them. They just sit in their houses all day. One of them came up to me last week and asked me to tell her husband to stop fighting. She said, 'He listens to you more than me,' and it's true. I've known him since he was three."

"What will you do if you don't get married?"

"Stay here."

"For the next 50 years?"

She shrugs.

"Don't you think this fighting has gotten out of hand?"

"Yeah, it has. We tell the guys to slow down, but they get loaded and who gives a fuck?"

"Would you shoot the guy who killed your brother?"

"I guess I have enough hate in me to do it."

"What about the guys who killed your cousins next door?"

"Them too."

It's early evening now and some of the vatos are coming into the basement. Yellow Rock got into a fight two days ago and tonight everyone expects a retaliation. Rachel and I know we are not wanted. When we leave, I notice the bullet holes scarring the shingles. Rachel says it's just blasts of buckshot but both of us quicken our steps. It is dusk, but all the little houses lined up in rows down the street, including Jeanette's, are absolutely dark, as if no one were home. The shades are drawn, there are no lights on inside, and an eerie stillness fills the growing darkness; even the crickets seem to have gone into hiding.

"Everyone's inside," whispers Rachel as we hurry to our car. "They're all in back. They know about the fight and they know there may be some shooting."

From a block away, a car door slams, and we both give an involuntary start.

* * *

I WAS VAGUELY AFRAID DURING MUCH OF THE TIME I SPENT IN THE BARRIOS. Sometimes I worried about getting caught in random crossfire, but mostly I worried that some of the vatos would hear about my comments on independence and orgasms and, in a macho fury spurred on by dust and booze, decide I was a threat. One of the girls I spoke with said she had to do a lot of talking to convince her home boys not to go after a Los Angeles Times reporter who wrote that his gang was "trying to make peace." I will not say that any of the vatos I heard about are trying to make peace, though some probably are. I'd rather talk about the courage of the girls like Chica who are going to try to make it in an alien world, without any money or friends, all alone. But maybe the last word should be that of the boy who was pitching in a baseball game I stopped to watch on my way to see Negra. The batter was poised and ready for the pitch, but the pitcher turned around to look at me.

"Hey," he said, tugging on his hat. "This ain't where you belong." He pressed the ball into the pocket of his glove, made the pitch, and the batter hit a foul, off to the left.

The pitcher turned to look at me again. I hadn't moved. "This is Mexican territory," he said. "Todo se paga." [All is avenged.]

* * *

***Note: a few days after this article appeared I got two calls on my answering machine from Vatos, both threatening me. One of them was in rhyme.