DESERT RATS

Story and photos by Tracy Johnston,

published in Image Magazine, San Francisco Examiner, 1991.

DOWN CARSON pass from San Francisco came the urban woman in a Japanese car filled with Diet Cokes and Western history books, country music filling up every sensual space but the view, which at the moment was beyond the grasp of anything mortal: a vast, high desert stretching east to Utah filled with mountain ranges dropped from the cosmos like rumpled pieces of silk. Dry lake beds appeared like mirages; great swirling circles in chalk. The woman headed into it all awash in melodrama, singing along with Willie Nelson:

"Mamas don't let your babies grow up to be

cowboys, They'll never stay home and they're

always alone, even with someone they love."

I KNEW I'D COME to another country when I stopped to read a plaque at the top of the Carson Pass that described Kit Carson as a "fearless Indian hunter." In San Francisco, we’d say a “murderer,” but no matter; it’s another century on the backside of the Sierra-Nevada mountain range.

I suggested this trip to the editor of a German magazine when he came to the Bay Area looking for travel stories. He suggested Highway One but I told him to forget the coastline with all those bed-and-breakfasts. "Highway 395," I said, "runs through a desert and is flanked by two of the world’s great mountain ranges. The landscape there is vast and primal. It reminds me of Tibet.”

The editor, no fool, got out a map and allowed as how he might just take that trip himself to see what I was talking about. We discussed how to get there (over Tioga or Carson Pass) and two weeks later I got a fax from Hamburg: “Write about Highway 395, from Bridgeport to Lone Pine, in the style of the great American adventure travel writing.” All this in l500 words. Whew.

* * *

The sun was just setting when Bridgeport rolled into view—a tiny green oasis in an expanse of desert scrub and volcanic cones—and I pulled over for a moment to watch the light show and take a few notes. I would beat the word limit, focus on a single adventure; a microcosmic incident. I would take the spare elegance of the landscape and make it rich with emotion -- distill the essence, write the Great Basin novel. OK. Haiku. It was only much later that night, alone in my motel room, that I thought about the Great Basin’s human landscape—the people who live alone in trailers in the scrub. The desert rats. I knew there must be women out there but it was easier to spot the men—the left-over drifters of the country music songs. “Geezers” my father used to call them; geezers and coots. I’d always imagined that they knew something important—how to be poor and crazy and happy, for instance.

At a coffee shop the next morning, I overheard one waitress telling another how to get to a local hot springs: “Take the middle fork by old Pete’s trailer and keep to the left.”

“Old Pete’s trailer,” I thought. “Perfect” The waitress was friendly and drew a map for me, and then I asked her about the cowboys I remembered seeing in the cafe 15 years ago.

The cowboys we get here, honey,” she said, “probably come from the Honeywell dude ranch down Twin Lakes road. People from Florida and New York pay a fortune to dress up in boots and hats and work at the ranch. We say they pay to shovel shit.”

The idea of New Yorkers shoveling shit in Ralph Lauren shirts appealed to me, and after breakfast I headed out to the ranch, which turned out to be a group of old cabins on a hill with a view that stretched east to Mecca. The first “dude” I met was Sam, age 15, wearing tennis shoes and glasses. He and his mom were having a great time, he said, and he took me to a kitchen cabin where some teen-agers were cooking pancakes and sausages for breakfast. I asked them who ran the place and they said Lenore Honeywell, who was 72 years old. Then they introduced me to Lenore’s granddaughter – a bouncy college student. I told her I was working for a German magazine and she gave me the rundown on the place.

Her great-grandfather had bought the land in 1870 and logged it to build Bodie (a nearby mining town of over 10,000 people at its height). When Bodie went bust, he started raising cattle.

“My grandmother built the cabins and opened the place up as a dude ranch during the Depression when beef went down to 3 cents a pound,” she said. “The price of beef fluctuates, but the dude ranch is steady income.”

“And people pay to work here?”

“Well – some of them help with round-up”

“I heard they really work. You know, dig fence posts and, well, shovel shit.”

“Not really. The people who come here want to ride. We have one thing that’s really good here, and that’s horses — I can definitely say that the horses are first-rate. Otherwise, we’re pretty basic.”

* * *

After checking the prices at Honeywell, which were dirt cheap, I slunk back to town wondering why I hadn’t seen through small-town prejudices about city slickers being pansy-assed; why I had gone after the cheap story in the first place. In penance, I sacrificed lunch and headed directly out to find the hot springs and Old Pete. I got the first turnoff alright, but everything else got confused because the dirt roads weren’t marked. Finally, just as it started to rain and I started to worry about my car getting stuck in the mud, I saw a stream and followed it to a flat plateau overlooking a deep valley and the Sawtooth Mountains. Someone had built a cement pool near a hot-water vent and in it was Mr. Jack Murray, about 60 years old, red as a beet, bearded, naked, and smiling.

Secret Hotsprings — without the bearded, naked, smiling Jack.

“WELCOME, LADY!” he cried. “MAN OH MAN, ARE YOU BEAUTIFUL. THIS IS MY LUCKY DAY.”

Telling myself I shouldn’t turn down an adventure, I got in the pool with Jack, whose red beard was glistening with water and steaming. But when he said, “Come over here and I’ll give you a foot rub,” I decided to set matters straight.

“I’m married and I’m not interested in anything sexual.”

“OK, OK. I promise I won’t make a move on you. I promise this will just be a very good foot rub.”

I decided getting my soles massaged was all in the line of the magazine business and settled down to listen to Jack talk about himself. He was a loner, he said; he painted signs for a living and had trouble making friends. “What do you do at night?” I asked. “I try to think of ways to pass the time,” he said.” Sometimes I think about going into the desert with a cup of water just to keep my lips dry – I could dehydrate there pretty easily…"

"Gee…”

“But, hey, I keep my humor and my smile.”

I told Jack about my search for a great American adventure, and he had an idea. “Take me with you,” he said. “I know where to find Indian petroglyphs; I know all the hot springs; I know where they filmed High Sierra, with Humphrey Bogart. Make me your assistant.”

Heading east, off Highway 395.

I wasn’t sure how much my German editor was prepared to pay for my 1,500-word haiku, especially since I had 1,400 words already written, but I decided to pretend that the editors in Hamburg were cheap. And so we sat in the hot springs and watched the storm clouds pass and the sun go in and out of the clouds, and when the rain turned wet we ducked down in the water. For five minutes or so we sputtered and laughed in a shower of hail.

“OH GOD, THIS FEELS GOOD,” Jack would say every now and then, or “It’s SO GREAT to be with a WOMAN,” and I’d get worried and start to get out, but then he’d say, “No, no stick around: I have another story.

I stayed because Jack was, in his way, a gentleman, and his stories were too good to miss. Most of them were about cosmic coincidences and Jack’s personal relationship to a parallel universe. Here’s the shortest one, which he called “The Candle and Lieutenant Kosmos”:

“I got my first inkling that God was paying attention to me when I was in the Army in Korea. A Lieutenant Kosman was coming to inspect our barracks and we all had to be ready. I remembered his name using a mnemonic device: Lieutenant Kosmos, the lieutenant from outer space. Now, for some reason we were supposed to keep our washbasin and candle in the bushes behind the barracks, and although I’d put the basin there earlier, I somehow overlooked the candle. When I found it, I just put it on my bunk under my helmet. When we heard Lieutenant Kosman was coming we all stood at attention, and then KERBANG! The door opened with a huge WHOMP! and Lieutenant Kosman stormed in, looking neither right nor left.

"Never breaking stride, he walked up the long aisle between the bunks and took out his swagger stick. He started swinging it over his head in a wide circle, and then, just before he reached my bunk, he poised it for a moment in mid-air, and SWOOSH – he made a sideways swipe that landed a direct hit on my helmet, sending it flying into space. The helmet hit the opposite wall and landed on the floor upside down where it rolled and rolled, making a noise – ping-ping-ping-ping. But Lieutenant Kosmos never looked at it, never broke his stride; he just kept walking, looking neither left nor right. When he reached the end of the aisle he kicked the door open, KERBOOM, and walked out.

"I looked over and saw my candle, still there on the bed, and heard my helmet still rolling on the floor. I picked up the candle and I knew I‘d been given a sign: The helmet is darkness, constriction, closing off. The candle is illuminated, light. God sent down Lieutenant Kosmos to give me my very first message: ‘Follow the light of your mind, don’t restrict it.’ And the best part, the part I REALLY LOVE, is that God did it with a sense of humor. God can tell a joke.”

There were lots more stories, including the one about the blonde, the marijuana joint and the parking lot behind the Gold Nugget in Reno, but finally my notebook got pretty soggy, not to mention my skin, and I said goodbye to Jack Murray, dried myself off, put on my clothes and got in the car. As I was leaving, Jack stood up in the pool and called out to me: “REMEMBER IF YOU CAN’T TELL MY STORIES RIGHT, LEAVE THEM OUT. DON’T CUT THEM.”

I gave him a thumbs-up, pressed down on the accelerator and did an unintended 180-degree spin in the mud. As I recovered, heart pounding, I heard Jack’s laughter. Then I saw him get out of the pool and start walking toward me so I gunned the motor and this time drove straight out. When I saw him in my rear-view mirror he looked like a tall piece of rhubarb, boiled and soft, just out of the steamer.

* * *

The next morning I got up before dawn and drove in the dark 20 miles south on 395. I wanted to get to Bodie, the Gold Rush ghost town, before sunrise.

I took the signed turn-off down a dirt road and after another 20 miles I ran into a gate and a booth with a sign on it announcing that Bodie was closed. The ghost town had become a State Historic Park and its hours were 10 to 5.

There was nothing I could do but wait, so I sat on the car and tried to imagine what Jack would do. I wrote a few haikus, did some stretching exercises and tried to see where the lizards went when they disappeared beneath the rocks. Then I sat still and thought some thoughts for awhile, and suddenly the thoughts turned into physical sensations. When I remembered Jack’s candle, my skin started tingling, and when I looked at the sky I discovered I could influence the cloud patterns. For a moment or two, I even heard distant voices, as if someone were giving a party on the other side of the ridge line.

Bodie — in a state of "arrested decay."

When I finally did get into Bodie, I found the place strangely unemotional. Its setting was spectacular – a desolate, windy pass – and the 50 or so buildings that had survived various fires were truly ghostly, in a state the Park Service calls “arrested decay.” But I didn’t stay long, probably because I’d already had my out-of-body experience. I took a few photos and moved on.

My next stop was very familiar – a huge (60-square mile) lake of eerie natural beauty about 30 miles farther south. Mono Lake is a mecca for amateur photographers and I’d come there with a tripod more than once. But this time, in pursuit of adventure, I stripped down to my bathing suit, stepped through the three-foot ring of black flies that buzzed the sides of the lake, walked on the famous tufa formations that look like miniature drip castles, and plunged into the water, which was full of trillions of tiny, red brine shrimp floating in the cool, blue water. As I swam away from shore I noticed that my feet were splashing more than usual -- they were out of the water somehow. And so was my head. For a moment it seemed that my sense of balance had gone awry, but then I remembered the salt. Like the Great Salt Lake, Mono has no outlet and is two-and-a-half times as salty as the ocean. I tried exhaling to see if I could sink, but I couldn’t.

* * *

A road has to go somewhere, I figured, so the next day I took an unmarked one just south of Mammoth Mountain (the largest ski area in California) and headed east, directly across the desert. It took me to what looked like an environmental sculpture created by Mad Max: a two-story-high heap of rusted metal that turned out to be the Mono County dump. Jerry Butler, an Irishman in his late 60s, greeted me. He ran the place and lived there alone in a trailer when he wasn’t with his woman, a Paiute Indian. From the chair where he sat for most of the day, he had a view so awesome I expected to see a herd of yaks.

Jerry invited me inside his trailer, where we drank beer and talked for a while beneath a wall covered with pin-ups of naked women. The next day I ended up spending several hours with him, from 3 o’clock in the afternoon to sundown at 8:30. We drove at least 50 miles of dirt roads, Jerry waving his arms and pointing at things and talking about “light” and “colors” and me stopping the car to get out and climb on rocks and generally lurch about like a 2-year-old. We went to a narrow-walled red-rock canyon full of snakes and shadows where he once ran out of gas and had to hike, in the moonlight, 17 miles to the nearest ranch. He showed me an old 19th-century mine shaft and a rock where a miner had sculpted a life-size image of himself, including hat and pickax.

On back roads with Jerry.

“Look what the bastards done,” Jerry said. The miner’s head and chest were pock-marked with bullet holes.

He took me to rattlesnake den where he used to catch snakes every spring and sell them to brokers from San Francisco, and we spent about an hour at some Indian petraglyphs in the middle of nowhere – four-and-six-and-eight-legged creatures dancing in the twilight as the sun turned the Great Basin fiery red. In the lingering light we drove on dirt roads to visit a friend of his, one of the Basque shepherds in the Basin who work the sheep ranches for five-year stints. But his camp was deserted – just a large flat circle in the scrub and a trash-filled fire pit. “He must just have moved,” Jerry said. “If he’d been here we would have had all the food we could eat. I’ve never known a Basque who didn’t make his own wine, cheese and bread.”

Finally, I turned on my headlights and we headed home, toward the highway in the growing darkness. “I just love showing you all this,” Jerry said. “I love it sooooooo much. Do you know I’m getting such a pleasure being here talking with you? Do you know that?”

“I’m having a good time, too.”

“You’re like me. You like to go out into nature and discover things.”

“Yes, I do.”

Jerry was on his sixth beer but, like Jack, he proved to be a gentleman. As we bounced along the dirt roads, the rabbit brush turning gold and a quarter-moon rising overhead, it seemed like a good time to play my Willie Nelson tape. Jerry closed his eyes, and when Willie started singing Help Me Make It Through the Night, he insisted I stop the car. “Let’s just listen to this,” he said. So we did.

Take the ribbon from your hair

Shake it loose and let it fall

Laying soft against your skin

Like the shadows from the wall.

Come and lay down by my side

‘Til the early morning light

All I’m taking is your time

Help me make it through the night.

“Why don’t you stick around?” Jerry said softly when the song was over and we were alone in the darkness, stars beginning to prick the evening sky. I had no interest in Jerry as a sexual companion, and I was loyal to my husband, but I appreciated the offer and the moment. Sexual advances are part of being female and traveling alone, and some of them are tender, I’ve found, and end up happily with just flirting. In the distance, the lights of the cars on Hwy 395 blinked and flashed, looking tiny in the desert vastness -- and something inside me expanded: I went into the darkness, beyond words, and felt a crazy kind of joy. It could have been a contact high off Jerry, who, like Jack was clearly having a good time, but I think it was more. It was Jerry and the place and the stars and the lights and the darkness and Willie. Too bad I had to cut the moment off so Jerry wouldn't get the wrong idea.

When I dropped him off at his trailer, Jerry got serious and said, "You know if things go bad back home you can always come here. I mean it. If you get depressed here all you have to do is go for a ride at sunset. I’ll even lend you my pickup.”

That night I drove another 20 miles down Highway 395 and checked into a motel in Big Pine where the road to the White Mountains beings. The owner said I had to be out early because a group called Holy Mountain Light, run by a German woman, had booked all five cabins for the week.

“They come here every year and one day they go up to White Mountain and spend the night alone in tents. It’s sorta – well, I have to say they all come back very happy. It’s not a survival kind of thing; something good just happens to them up there.”

* * *

My last day on 395 I drove to Lone Pine. The High Sierra ends at this point (just south of Mount Whitney), and in another 180 miles the road hits the outskirts of greater Los Angeles.

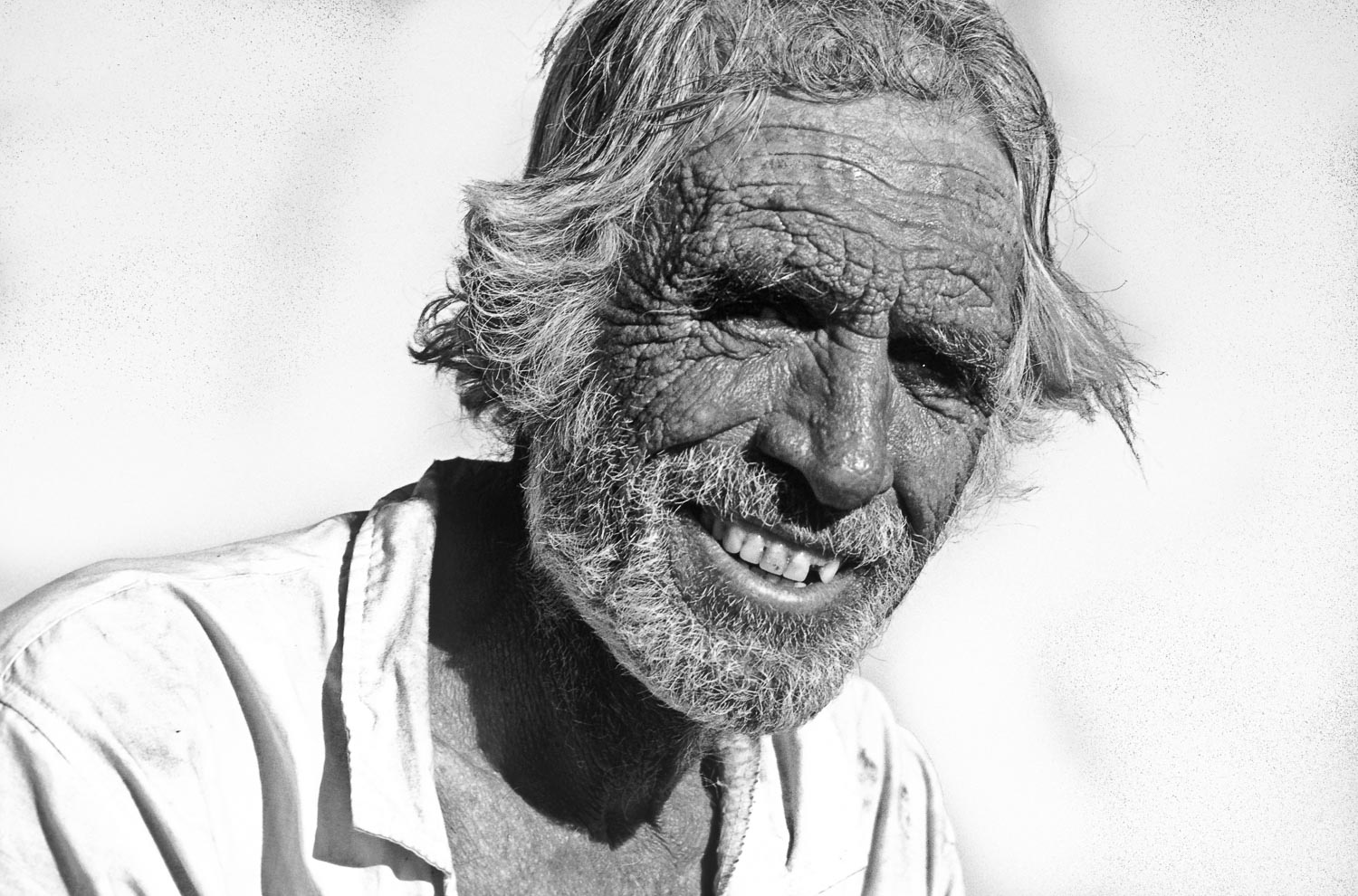

I ran into Gene Churchill in Lone Pine, in a corral where he was feeding horses in exchange for the use of a tiny aluminum trailer. I stopped and introduced myself because, under his cowboy hat, Gen’s face was so weathered it was frightening. His eyes, deep inside two leathery sockets, were invisible, and the folds and caverns of his wrinkled forehead seemed inhuman.

Gene Churchill, 69.

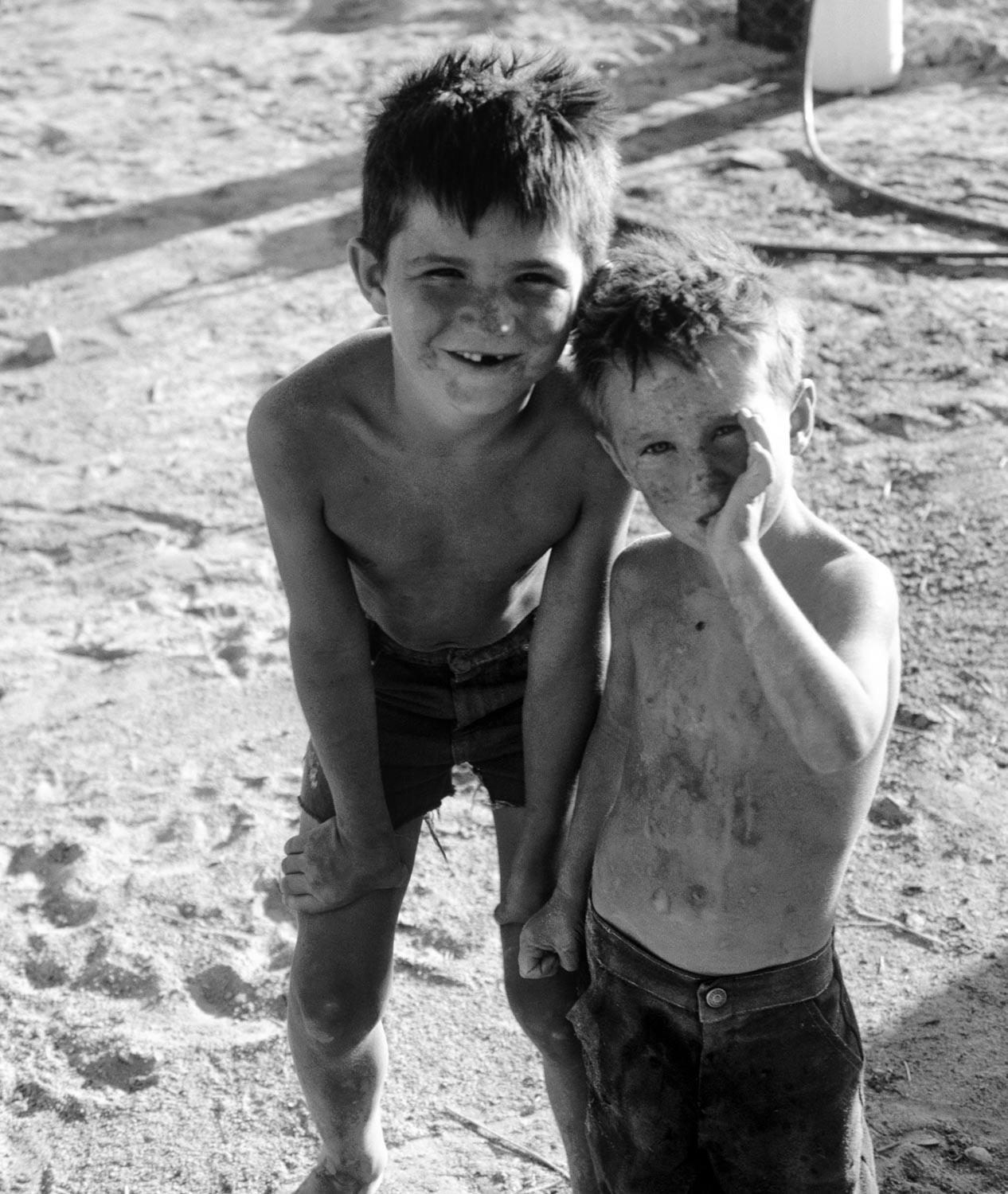

But Gene tipped his hat and welcomed me. He was 69, it turned out, and though he walked stiffly and spoke slowly (I lost my train of thought during many of his long, amiable pauses), he had undertaken a new life. He was a retired horse packer, it turned out, which is about as low as you can get on the cowboy circuit, and had come to Lone Pine to raise two young boys cheaply, on Social Security and veteran’s benefits. The boys were 4 and 7, sandy-haired and freckled, shoeless and shirtless, sunburned, and while we talked they ran around the corral kicking and showing off like puppies.The boys’ mother (Gene’s third wife) left him and the kids, he said. “She wasyoung and educated and came from a very wealthy family. But after I married her, I found out she was on drugs. I read her diary after she left and found out she’d even been a prostitute. Can you imagine that? A girl from a wealthy family with a good education becoming a prostitute?

I squirmed as he talked since the boys were listening, and said, finally: “Well, I’m sure she loves the boys. She can’t help what she’s doing if she’s an addict.”

"I don’t think she loves them at all,” he replied. “She cares more about the drugs than she does for them. If she loved them, I’d at least know where she was.” He had a point.

Gene Churchill's two boys.

I tried to talk to Gene a little about the remarkable landscape, but he wasn’t interested. He wanted to tell me what he was feeding the boys, how he was going to get $2,000 in veteran’s pay and rent an apartment, how the boys’ wealthy grandmother had told him she’d pay for their college education. Gene wanted my German readers to know he was responsible.

When I finally drove off, the oldest boy started running after me across the flats. The 4-year-old tried to follow but kept having to stop and pick up his pants, which fell down with comic regularity. I drove slowly, keeping the 7-year-old in my rear view mirror, and was surprised to see that he didn’t give up. He ran a quarter-mile flat out, I think – leaping over gullies and rocks and weaving through scrub, racing across the prickly desert in the hot sun with his bare feet.

When we got to the highway and I stopped, he was so out of breath he couldn’t talk; he could barely stand up.

“What a runner!” I said. “That was really great.” He grinned and gasped and kept grinning as I groped for something to say.

“You know,” I said finally, “I’m sure your daddy’s going to take real good care of you.”

He looked startled and backed away a few feet, then looked up at me, his eyes darting wildly. He was smiling – a crazy, happy grin. As I pulled out onto 395, I watched him in the mirror. He stood by the edge of the highway, watching me, until I got all the way through Lone Pine.

* * *

Later that afternoon, I took off for Las Vegas via Death Valley, where the temperature was supposedly 119. On my way, I stopped to finish off a roll of film and saw a figure that looked like Lawrence of Arabia running toward me from the east. It turned out to be a runner wearing a white long-sleeved shirt, long white pants and a white burnoose. I dropped my camera by the side of the road and jogged alongside him for awhile, wondering how soon I’d collapse in the heat. (Strangely, jogging in a blast furnace is no more intolerable than standing in it.)

The man was in a race, it turned out – an annual run from the lowest point in the United States (Badwater in Death Valley) to the highest (Mount Whitney).

“I gotta be crazy,” he said (pant pant)

“This is a good place to do it.”

“The last guy I saw on the road was traveling in a wheelchair (pant pant). He offered me a beer and challenged me to a race.”

“Wow” “Where is he?”

“Back there. He’s an Indian, I think. A crazy Indian.”

I took the opportunity to stop. I wanted to photograph the crazy Indian with a beer in a wheelchair. As the runner pulled ahead, looking like a great, flapping ghost, I looked back and saw a tiny moving speck But by the time I got to the car and found my binoculars, the speck had disappeared.

* * *

Back home in Oakland, after a flurry of faxes, it became clear that the German translator of my much-longer-than-1,500-word opus was eliminating the characters and leaving in the “where to go and what to eat” material. I didn’t protest, remembering what Jack had said: Don’t tell them unless you can do it right. I’ve tried to do that here.

Still, there are some stories I still haven’t told – other things that happened to me on 395, like the afternoon I spent dangling in a broken gondola at Mammoth Mountain Ski Resort. But if you want more stories, you can easily get them yourself; The Great Basin has a surfeit. And if you want some more of Jack Murray’s stories, give him a call. He told me to tell my readers that his number is in the Lee Vining telephone book. ⚀